In the past, viruses and computer threats were created simply for the sake of it. Sometimes these threats would wipe your hard drive clean—just to let you know you’d been owned. This is not the case anymore; nowadays most of the threats we see are profit-oriented and try to keep a very low profile so that they aren’t easily detectable by security software.

Backdoor.Tidserv does a very good job in that sense, especially with the latest version (TDL3), which uses an advanced rootkit technology to hide its presence on a system by infecting one of the low-level kernel drivers and then covering its tracks. While the rootkit is active there is no easy way to detect the infection, and because it goes so deep into the kernel, most users cannot see anything wrong in the system.

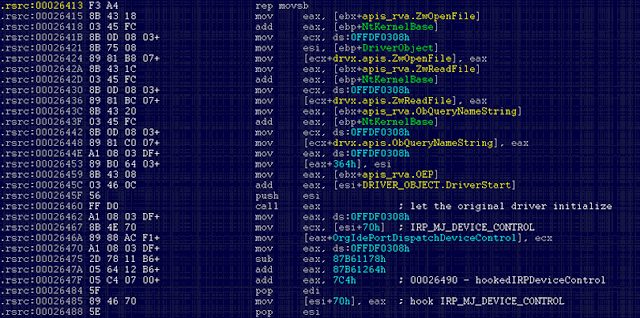

Most of the time the driver chosen by Tidserv to be infected is “atapi.sys,” but that may vary depending on the hardware configuration. One of the very things the infected driver does when it is loaded by the operating system is to retrieve critical API addresses so that it can allocate memory to load the actual malicious code:

These APIs are retrieved via hard-coded relative virtual addresses (RVAs) into the kernel module, which are calculated at the infection time. Microsoft recently released a kernel patch that addressed a non-related issue (MS10-015 / KB977165), which updates the kernel modules. They also released a blog about blue screen issues after applying this patch.

What seems to have happened in Tidserv’s case is that after this update, the RVAs for the above mentioned APIs changed—therefore causing the infected drivers out there to call invalid addresses and, in turn, cause blue screens every time Windows boots up:

Even worse, because the infected driver is critical for system boot-up, Windows will not boot in Safe Mode either. However, there is still hope for the users who get stuck in this infinite loop of BSoD, in the sense that they are not required to reinstall everything from scratch, but only the infected driver (from a known, clean source). And, here is an example for the most commonly infected system driver, atapi.sys:

- Boot from a clean source (e.g. Windows CD)

- Locate the infected partition, which is normally the boot partition

- Replace atapi.sys in %Windir%\system32\drivers with the clean backup copy

- Reboot

Here’s a list with the most common driver names infected by the rootkit, which can be used in the above process:

- atapi.sys

- iastor.sys

- idechndr.sys

- ndis.sys

- nvata.sys

- vmscsi.sys

We are aware that the blue screens may be caused by other good or bad kernel mode applications that were relying on hard coded addresses, but Tidserv is one of the most prevalent threats that may cause this problem. Symantec detects these infected drivers on disk as Backdoor.Tidserv!inf, but recommends that the files are replaced manually, since attempting to remove the file automatically may render the system unbootable.

In conclusion, it seems that no matter how complex and stealthy a threat may be, it may be given away by such a small thing as a software update. This should be a lesson for the authors that developed the rootkit—but more importantly or the victims that fell for the back door.

Omid Farhang

Omid Farhang