With Google owning YouTube, the Internet’s principal delivery system for Flash-based video, it was perhaps inevitable that the company would bundle the Flash plug-in with its Chrome browser. The announcement came today from both Google and the team developing the open source Chromium component on which Chrome is based.

The move now officially places Google in contention with proponents of HTML 5, who had held out a glimmer of hope for a non-proprietary, non-plug-in video format for the standard’s new [VIDEO] element. In its blog post today, the Chromium team indirectly blamed the standards process for not having solved what it perceives as the problem of specifying how plug-ins should operate, and credits Mozilla — which makes Firefox — with helping to rectify that issue.

“The traditional browser plug-in model has enabled tremendous innovation on the Web, but it also presents challenges for both plug-ins and browsers,” reads today’s post from Google Vice President for Engineering Linus Upson. “The browser plug-in interface is loosely specified, limited in capability and varies across browsers and operating systems. This can lead to incompatibilities, reduction in performance and some security headaches.”

Upson credits Mozilla’s efforts to upgrade and improve the old Netscape plug-in API model, still called NPAPI. This model currently enables out-of-process plug-ins to operate essentially independently from the browser. Historically, it’s this independence that has been exploited by malicious users infiltrating victims’ systems through Adobe Flash. Under the new system proposed by Mozilla, code-named “Pepper,” processes launched through the browser would run through threads that are routed completely independently of browser and renderer threads. Specifically, the new thread model would block browser threads when plug-in threads are active, and vice versa, so that one would never have access to the other.

Consider it a kind of “anti-multithreading” that may very well be necessary in the age of Web applications.

But by citing Mozilla as the leader in this effort, Google may effectively be ceding responsibility for solving some of the most critical Flash security issues to date, to Mozilla. Until then, Upson concedes that the first Chrome dev build to contain the Flash plug-in will not yet have resolved a potential security risk: the separation between the Chrome tab processes and the Flash runtime. Part of Google’s (originally) innovative security model was its division of browser tabs into separate processes, so that when one tab crashes, the main browser remains stable.

One of the unanticipated side-effects of this model deals with Chrome’s approach to add-ons: They too are separate processes, all of which identify themselves to the operating system as Chrome. The screenshot above shows a list of active processes from Sysinternals’ Process Explorer, with the latest Chrome dev build 360.4. There’s only one tab running the Acrobat.com page, but note that Chrome appears twice in the list. That second instance appears to be the Chrome sandbox wrapped around the Flash add-on.

But it’s not. As Google’s Upson said today, despite appearances, the Flash instance which that second item appears to encapsulate is not completely covered by Chrome’s sandbox — its safe operating environment. There’s obvious reasons for that: Here, Flash Web apps are hosted in the client by the AIR runtime. There should only be one instance of AIR running within a client.

The reasons why were outlined in a 2008 white paper (PDF available here) written by a trio of university researchers who were employed by Google to design Chromium. It’s in “The Security Architecture of the Chromium Browser” that the designers explain the division of the browser kernel, which interacts with the operating system, from the renderer which is isolated in the sandbox. Plug-ins must run independently of the sandbox in order to fulfill the needs of their manufacturers, the group stated, even though doing so introduces a potential vulnerability. Notice which plug-in they picked as their case-in-point:

In Chromium’s architecture, each plug-in runs in a separate host process, outside both the rendering engines and the browser kernel. In order to maintain compatibility with existing web sites, browser plug-ins cannot be hosted inside the rendering engine because plug-in vendors expect there to be at most one instance of a plug-in for the entire web browser. If plug-ins were hosted inside the browser kernel, a plug-in crash would be sufficient to crash the entire browser.

By default, each plug-in runs outside of the sandbox and with the user’s full privileges. This setting maintains compatibility with existing plug-ins and web sites because plug-ins can have arbitrary behavior. For example, the Flash Player plug-in can access the user’s microphone and webcam, as well as write to the user’s file system (to update itself and store Flash cookies). The limitation of this setting is that an attacker can exploit unpatched vulnerabilities in plug-ins to install malware on the user’s machine.

Users could try running Chromium (and later Chrome), the group suggested, using the command line switch --safe-plugins, which would place all plug-ins under the protection of the renderer’s sandbox. But they’ll likely crash, they warned.

To address that problem, Adobe’s senior director of Flash engineering, Paul Betlem, said in a blog post todaythat his team will work with both Google and Mozilla to replace and improve NPAPI. “While the current NPAPI has served the industry well, it lacks the flexibility and power to support the pace of innovation we see ahead,” Betlem wrote. “We expect that the new API specification will offer some distinct benefits over the current technology available.”

One foreseeable outcome of this collaboration could very well be a community where at least some plug-ins are compatible with both Chrome and Firefox simultaneously. But another outcome that Adobe’s Betlem points to is a certain kind of unification, not just of the security model but of how the browser presents itself to the world. Think of it as “the Flash browser.”

“The new API is being designed with the flexibility to allow plug-ins to more tightly integrate with host browsers,” wrote Betlem. “The new plug-in API will provide performance benefits since the host browser will be able to directly share more information about its current state.”

Reaction to Adobe’s and Google’s move today was mixed on Google’s forums, with about two-thirds of respondents against the bundling and one-third vocally in favor. As supernova_00 wrote this morning, “Ugh. And here I thought we were all getting close(ish) to completely ditching Flash, and you guys decide to bundle Flash with Chrome. What the hell happened to open standards?”

Plus this from contributor Daniel Hansen: “Just when we thought that Google was the champion of HTML 5, they turn around and partner with Adobe on Flash to ensure that the Web remains a mess of proprietary brain damage.”

Support for the move centered around the notion that Flash is simply a fact of life on the modern Web that no arbitrarily imposed standard is likely to change overnight, or even in the next decade. “People must be really dumb if they think HTML 5 is going to kill Flash,” wrote Gabriel. “It’s used for so-o-o much more than cats playing piano. The sooner you realize this, the more Google’s move makes sense.”

There was also this from contributor Troy: “How is Flash not an open standard? The bytecode format of [Shockwave] SWFs is published. There are open-source tools for producing SWFs. The tool chain is open-source and free. The player is available on the three major desktop OSs, and now on many mobile devices, as well as several video game consoles. Its virtual machine is open-sourced. Sure, it’s not standard-certified by some international organization, but neither is HTML 5 (yet) nor is CSS3 (yet). It is a de facto standard, used by more Web sites and users than HTML 5, CSS3, Canvas, etc. Come on, folks, let’s be pragmatic.”

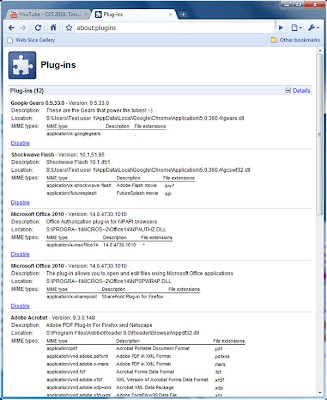

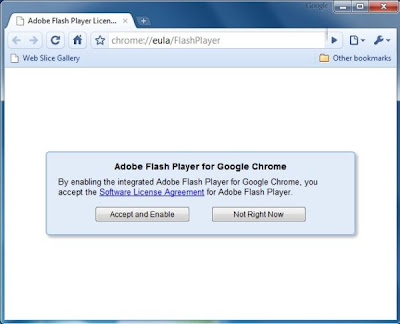

The bundling of Flash with Chrome does not change the relationship between the component and the browser, as indicated by the about:plugins page above. Notice its format changed with this latest dev build; it now includes (highly requested) Disable links that let you turn off plug-ins without uninstalling them. However, bundling Flash did add 2.4 MB to Chrome 5’s download size, plus a single new question to the startup procedure (shown below). In the dev build, to start using the Flash plug-in that’s distributed with the browser, you run Chrome from the command line, adding the switch --enable-internal-flash.

Omid Farhang

Omid Farhang